(17/21) The Math Behind VC Funds, Metrics, Benchmarks, and What It Means for Your Investments

Welcome back to "VC Mastery: Your Ultimate Guide to Venture Capital Investing between Science and Art, Unlocking the Secrets of Successful Investing through Data, Insights, and Intuition." In today’s post, we’ll delve into the mathematical foundations that underpin venture capital (VC) funds. Understanding these financial mechanics is crucial for anyone looking to excel in venture capital, as they provide the framework for evaluating fund performance, managing risk, and optimizing returns. We’ll cover the key elements of the VC financial model, explore important metrics and benchmarks, explain the J-Curve phenomenon, and discuss the power law that governs returns in venture capital.

1. The Math Behind VC Funds

At its core, a venture capital fund is a financial vehicle designed to pool capital from Limited Partners (LPs) and invest it in early-stage companies with the potential for high growth. The math behind VC funds involves understanding how capital is raised, invested, and returned, and how these processes impact the overall performance of the fund.

Key Concepts:

Committed Capital: The total amount of capital that LPs have agreed to invest in the fund. This capital is usually called down over time as the fund makes investments.

Capital Calls: The process by which the fund manager requests the committed capital from LPs as needed for investments or to cover management fees.

Carried Interest (Carry): The share of profits that the fund manager (General Partner or GP) earns after returning the capital invested by LPs. This is typically around 20% of the profits and is a key incentive for fund managers.

Management Fees: The fees charged by the GP to cover the operational costs of managing the fund. These fees are usually around 2% of the committed capital per year and are paid by the LPs.

2. VC Fund Financial Model

The financial model of a VC fund is built around the lifecycle of capital—from the initial commitment by LPs to the eventual return of capital plus profits. Understanding this model helps in forecasting fund performance and managing cash flows.

Key Elements:

Investment Period: The period during which the fund actively invests in startups, typically the first 3-5 years of the fund’s life. During this time, the fund manager identifies opportunities, conducts due diligence, and deploys capital.

Harvest Period: The period following the investment phase, during which the fund focuses on managing and eventually exiting its investments. Exits may occur through mergers, acquisitions, IPOs, or secondary sales.

Cash Flows: VC funds are characterized by irregular cash flows. Early years often see negative cash flows due to capital calls and management fees, while positive cash flows occur later as investments are exited and returns are distributed.

Distribution Waterfall: The sequence in which returns are distributed to LPs and GPs. This typically starts with returning the invested capital to LPs, followed by the payment of the preferred return (if any), and finally the distribution of carried interest to the GP.

For a detailed step-by-step guide on how to build your fund’s financial mode on Excel or Google Sheets with a robust template you can read OpenVC’s post on this here: https://openvc.app/blog/how-to-model-a-venture-capital-fund

3. VC Fund Analytics, Metrics, and Benchmarks

Analyzing the performance of a VC fund involves tracking a range of metrics and comparing them against industry benchmarks. These metrics provide insight into the health and success of the fund.

Key Metrics and Their Equations:

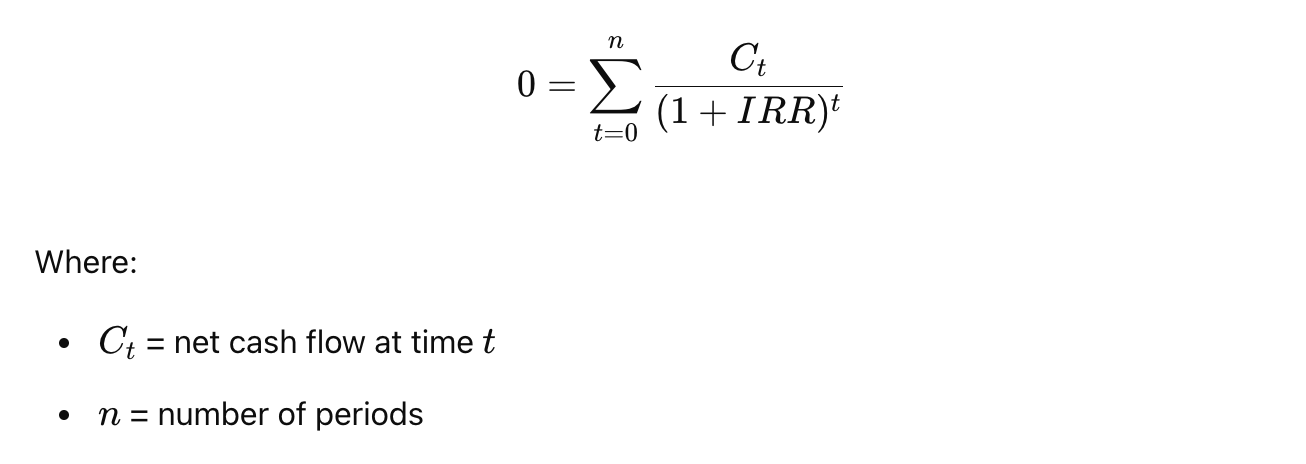

Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

Definition: IRR is the discount rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows (both positive and negative) from an investment equal to zero. It represents the annualized rate of return on an investment over its lifetime.

Importance: IRR is a crucial metric for comparing the profitability of different investments, as it accounts for the time value of money. It helps VCs assess whether the potential returns justify the risks and timeline of the investment.

Equation: The IRR is found by solving the following equation:

Total Value to Paid-In (TVPI):

Definition: TVPI measures the total value created by a fund relative to the total capital invested by LPs. It includes both realized (distributed) and unrealized (residual) value.

Importance: TVPI provides a comprehensive view of a fund’s performance by considering both realized and unrealized gains. It’s a key metric for LPs to evaluate the overall success of their investment in the fund.

Equation:

Distribution to Paid-In (DPI):

Definition: DPI is the ratio of the capital returned to LPs to the total capital they have contributed. It focuses on realized returns and indicates how much cash has been distributed relative to the invested capital.

Importance: DPI is an important metric for LPs to track how much of their invested capital has been returned to them, offering insight into the fund’s liquidity and cash-on-cash returns.

Equation:

Residual Value to Paid-In (RVPI):

Definition: RVPI measures the current value of the remaining investments in the fund relative to the capital paid in by LPs. It reflects the unrealized portion of the fund's value.

Importance: RVPI helps LPs assess the potential future returns from the fund’s remaining investments, giving a sense of the unrealized value in the portfolio.

Equation:

Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC):

Definition: MOIC is a simple metric that shows how much money has been returned relative to the amount invested. It does not account for the time value of money.

Importance: MOIC is a straightforward measure of the overall return on investment, making it useful for quick comparisons between different investments or funds.

Equation:

Gross vs. Net IRR:

Definition: Gross IRR is calculated before deducting management fees and carried interest, while Net IRR is calculated after these deductions, representing the actual return to LPs.

Importance: Understanding both Gross and Net IRR is important for evaluating the effectiveness of fund management. Gross IRR provides a view of the fund’s raw performance, while Net IRR reflects the actual returns received by LPs after all costs.

Equations:

Gross Multiple (Gross TVPI):

Definition: Gross Multiple (or Gross TVPI) is the total value multiple calculated before deducting management fees and carried interest. It measures the total value created by the fund relative to the total capital invested by LPs, providing a gross measure of performance.

Importance: Gross TVPI provides a clear view of the fund’s ability to create value before any fees or carried interest are deducted, offering insights into the overall effectiveness of the investment strategy.

Equation:

Net Multiple (Net TVPI):

Definition: Net Multiple (or Net TVPI) is the total value multiple calculated after deducting management fees and carried interest. It provides a net measure of performance from the perspective of the LPs.

Importance: Net TVPI is crucial for LPs as it reflects the actual return on their investment after all costs, providing a realistic measure of the fund’s success.

Equation:

Paid-In Capital (PIC):

Definition: Paid-In Capital refers to the total amount of capital that LPs have contributed to the fund at any given time.

Importance: Understanding PIC is essential for calculating various performance metrics like DPI, TVPI, and RVPI. It also helps in tracking how much of the committed capital has been deployed.

Vintage Year

Definition: The vintage year of a VC fund refers to the year in which the fund was established and made its first investment. It is often used as a reference point for benchmarking fund performance against other funds started in the same year.

Importance: The vintage year is important because it provides context for performance comparisons. Funds with the same vintage year may face similar market conditions, making it a relevant benchmark for evaluating performance.

Residual Value

Definition: Residual Value is the estimated value of the fund’s remaining investments that have not yet been realized or exited. It is a component of the TVPI and RVPI metrics.

Importance: Residual Value is critical for assessing the potential future returns of a fund. It gives LPs an idea of the unrealized gains that could still be generated from the remaining investments.

Preferred Return (Hurdle Rate)

Definition: A Preferred Return, or Hurdle Rate, is the minimum return that LPs are entitled to before the GP can earn carried interest. It ensures that LPs receive a certain level of return before profits are shared.

Importance: The Preferred Return aligns the interests of GPs and LPs by ensuring that the fund must perform well before the GP can benefit from carried interest. It acts as a safeguard for LPs.

Catch-Up Provision

Definition: A Catch-Up Provision allows the GP to catch up on their share of profits (carried interest) after the LPs have received their preferred return.

Importance: This provision is important because it incentivizes GPs to achieve returns that exceed the preferred return, benefiting both LPs and GPs by ensuring that the fund reaches certain performance thresholds.

Loss Ratio

Definition: The Loss Ratio measures the proportion of investments in a VC portfolio that have resulted in a loss relative to the total capital invested.

Importance: The Loss Ratio is a critical metric for understanding the risk profile of a VC fund. A high Loss Ratio may indicate a need for better due diligence or investment strategy, while a low Loss Ratio suggests effective risk management.

Public Market Equivalent (PME)

Definition: PME is a method used to compare the performance of a private equity or VC fund with public market indices. It adjusts the cash flows of the private investment to simulate what the returns would have been if the capital had been invested in the public market.

Importance: PME is valuable for LPs who want to assess whether investing in a VC fund has outperformed or underperformed compared to public markets. It provides a benchmark to evaluate the opportunity cost of private investments.

Capital Deployment Rate

Definition: This measures the speed at which a VC fund deploys its committed capital into investments.

Importance: Monitoring the Capital Deployment Rate is crucial for ensuring that the fund remains on track with its investment strategy and timeline. A balanced deployment rate helps in managing cash flow and achieving diversification.

Exit Multiple

Definition: Exit Multiple is the multiple of the amount received at exit relative to the amount invested in a company.

Importance: The Exit Multiple is a key indicator of the success of an individual investment. It helps VCs assess the profitability of each exit and contributes to the overall performance of the fund.

Portfolio Company Concentration

Definition: This refers to the percentage of the fund’s total capital invested in its top-performing companies.

Importance: Managing concentration risk is vital for ensuring that the fund’s success is not overly dependent on a small number of portfolio companies. A well-diversified portfolio can help mitigate the impact of any single company’s underperformance.

Benchmarks:

Cambridge Associates Benchmarks: One of the most widely used benchmarks in the VC industry, providing performance data for funds across various vintages, stages, and geographies.

Preqin: Another leading provider of performance benchmarks and analytics for private equity and venture capital funds.

4. The J-Curve

The J-Curve is a visual representation of the typical cash flow pattern of a VC fund over time. It shows that in the early years, funds often experience negative returns due to capital calls and management fees, but as investments mature and exits occur, returns increase sharply, forming a “J” shape.

Understanding the J-Curve:

Early Losses: In the initial years, funds are characterized by negative returns as capital is deployed, and management fees are paid, but no exits have yet occurred.

Recovery and Gains: As the portfolio matures and successful exits occur, the fund’s value increases, leading to positive returns. The timing and magnitude of these exits determine the steepness of the curve.

Implications for LPs: LPs must be patient and understand that early negative returns are normal and that the real performance of the fund is often only visible in the later years.

5. The Power Law of VC Funds

The power law is a fundamental concept in venture capital that describes how returns are distributed across a portfolio. In a typical VC fund, a small number of investments generate the majority of the returns, while many investments may break even or fail.

Key Insights:

Skewed Returns: In venture capital, returns are not normally distributed. Instead, they follow a power law distribution, where a few “home runs” generate outsized returns that drive the overall performance of the fund.

Portfolio Construction: Understanding the power law is critical for portfolio construction. VCs must make enough investments to increase the likelihood of hitting those high-returning companies, while also managing the risks of the many investments that will not generate significant returns.

Implications for Fund Management: Fund managers need to be comfortable with a high failure rate in their investments, knowing that the success of the fund will likely depend on a few standout companies.

Conclusion

The math behind venture capital is both complex and fascinating, driving the financial dynamics that make VC such a unique and challenging asset class. From understanding the cash flow patterns depicted by the J-Curve to recognizing the importance of the power law in portfolio construction, mastering these concepts is essential for anyone looking to succeed in venture capital.

In the next post, we’ll continue to explore advanced topics in venture capital, diving deeper into fund management strategies and performance optimization.

Happy investing!